Desert food web examples showcase the fascinating interconnectedness of life in some of the planet’s harshest environments. These webs, though seemingly simple, are intricate systems where every organism plays a vital role. From the hardy plants that anchor the soil to the apex predators that keep populations in check, each species is uniquely adapted to survive and thrive in the face of extreme heat, limited water, and scarce resources.

This exploration will delve into the fundamental components of desert food webs, examining the producers, consumers, and decomposers that drive these ecosystems. We’ll uncover the remarkable adaptations that allow desert organisms to persist, from the water-storing capabilities of cacti to the nocturnal hunting strategies of desert foxes. Furthermore, we’ll highlight specific examples from the Sonoran and Sahara Deserts, revealing the intricate relationships that define these unique environments.

Introduction to Desert Food Webs

A food web illustrates the complex feeding relationships within an ecosystem, showing how energy and nutrients flow between organisms. In a desert ecosystem, these webs are shaped by the extreme conditions of limited water, intense sunlight, and fluctuating temperatures. Understanding these webs is crucial to comprehending the delicate balance and resilience of desert life.The structure and function of desert food webs are significantly influenced by the harsh environment, where the availability of resources such as water and food can vary dramatically.

Examine how buffalo ny food bank can boost performance in your area.

Organisms have evolved specific adaptations to survive and thrive in these conditions, leading to unique interactions within the food web.

Fundamental Components of a Desert Food Web

Desert food webs, like all ecosystems, are composed of various interacting components that determine the flow of energy and matter. These components are categorized based on their roles in obtaining and utilizing resources.

- Producers: These organisms, primarily plants, are the foundation of the desert food web. They convert solar energy into chemical energy through photosynthesis. Examples include:

- Cacti, such as the saguaro, which stores water in its tissues and has a long lifespan, providing a stable food source.

- Succulents, which are adapted to store water and withstand drought conditions.

- Desert shrubs and grasses, which often have deep root systems to access groundwater.

- Consumers: Consumers obtain energy by feeding on other organisms. They are categorized by their trophic level.

- Primary Consumers (Herbivores): These animals eat producers. Examples include:

- Desert rodents, such as kangaroo rats, which consume seeds and plant matter.

- Insects, such as grasshoppers, which feed on desert plants.

- Herbivorous reptiles, like desert tortoises, which graze on grasses and other vegetation.

- Secondary Consumers (Carnivores): These animals eat primary consumers. Examples include:

- Snakes, such as sidewinders, which prey on rodents and other small animals.

- Lizards, like the Gila monster, which consume insects and small vertebrates.

- Scorpions, which feed on insects and spiders.

- Tertiary Consumers (Top Predators): These animals are at the top of the food chain and often prey on secondary consumers. Examples include:

- Coyotes, which hunt rodents, reptiles, and sometimes larger animals.

- Hawks and eagles, which prey on various animals, including rodents and reptiles.

- Owls, which are nocturnal hunters of rodents and other small prey.

- Primary Consumers (Herbivores): These animals eat producers. Examples include:

- Decomposers: Decomposers break down dead organisms and waste, returning essential nutrients to the soil. Examples include:

- Bacteria, which are crucial for breaking down organic matter.

- Fungi, which also play a vital role in decomposition.

- Detritivores, such as certain insects and worms, which feed on dead organic material.

Influence of the Desert Environment

The harsh desert environment significantly influences the structure and function of the food web, leading to unique adaptations and interactions.

- Water Scarcity: The limited availability of water affects all organisms.

- Plants have evolved adaptations such as deep roots, water-storing tissues, and reduced leaf surfaces to conserve water.

- Animals have developed behavioral adaptations like nocturnal activity, efficient kidneys to minimize water loss, and the ability to obtain water from food.

- Intense Sunlight and Temperature Fluctuations: These factors influence the activity and survival of organisms.

- Many animals are active at dawn and dusk or during the night to avoid extreme heat.

- Plants may have reflective surfaces or spines to reduce heat absorption.

- Nutrient Cycling: Nutrient availability is often limited, impacting the entire food web.

- Decomposers play a critical role in recycling nutrients, making them available to producers.

- The slow decomposition rate in some deserts can affect the availability of nutrients.

- Species Adaptations: Adaptations play a key role in the survival and interactions within the food web.

- Camouflage helps predators and prey avoid detection.

- Specialized diets and foraging strategies allow organisms to utilize available resources efficiently.

Producers in Desert Ecosystems

Producers form the foundation of desert food webs, converting sunlight into energy that fuels the entire ecosystem. These organisms, primarily plants, are uniquely adapted to survive in the harsh conditions of deserts, where water is scarce and temperatures fluctuate dramatically. Their ability to thrive in these environments is critical for supporting the diverse animal life that depends on them.

Primary Producers Commonly Found in Deserts

The primary producers in deserts are predominantly plants, though some photosynthetic bacteria and algae can also be found, especially in areas with occasional moisture. The most significant producers are vascular plants, including various types of:

- Cacti: These are iconic desert plants, particularly in the Americas, known for their water-storing stems and spines.

- Succulents: Many succulents, such as agave and aloe, store water in their leaves or stems.

- Shrubs: Various drought-tolerant shrubs, like creosote bush and sagebrush, are common.

- Grasses: Some grasses have adapted to survive in deserts, often exhibiting deep root systems.

- Annuals: Many annual plants complete their life cycle during brief periods of rainfall, producing seeds that remain dormant until the next favorable conditions.

Adaptations of Desert Producers

Desert plants have evolved a variety of adaptations to cope with the challenges of their environment. These adaptations allow them to conserve water, withstand extreme temperatures, and efficiently capture sunlight. Key adaptations include:

- Water Storage: Many plants, such as cacti and succulents, have specialized tissues in their stems or leaves to store large quantities of water.

- Reduced Leaf Surface Area: Some plants have small leaves or spines, which minimize water loss through transpiration. For instance, the spines of cacti reduce the surface area exposed to the sun.

- Deep or Extensive Root Systems: Deep roots allow plants to access groundwater, while extensive shallow roots can quickly absorb rainfall.

- Waxy Cuticles: A waxy coating on leaves and stems reduces water loss through evaporation.

- CAM Photosynthesis: Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) is a photosynthetic pathway that allows plants to open their stomata (pores) at night, reducing water loss during the day.

- Dormancy: Some plants enter a dormant state during dry periods, conserving energy and resources until conditions improve.

Specific Desert Plants, Their Role, and Nutrient Acquisition

Desert plants play a vital role in the food web, providing food and shelter for various animals. They obtain nutrients from the soil through their roots, which absorb water and dissolved minerals. Photosynthesis, the process of converting sunlight into energy, is crucial for their survival and for supporting the entire ecosystem.

- Creosote Bush (Larrea tridentata): This shrub is widespread in North American deserts. It produces a distinctive odor and has small, waxy leaves that reduce water loss. It obtains nutrients from the soil through its extensive root system. It serves as a food source and shelter for many desert animals, including rodents and insects.

- Saguaro Cactus (Carnegiea gigantea): The Saguaro is a giant cactus found in the Sonoran Desert. It stores large amounts of water in its stem and has shallow roots that spread widely to absorb rainfall. It provides food (nectar and fruits) and shelter for birds, bats, and other animals. Its nutrient acquisition is similar to other plants, absorbing nutrients from the soil through its roots.

- Prickly Pear Cactus (Opuntia spp.): Prickly pear cacti have flat, pad-like stems covered in spines. They store water in their stems and have a shallow root system. They are a food source for various animals, including desert tortoises and javelinas. Nutrients are absorbed from the soil via their roots.

- Desert Marigold (Baileya multiradiata): This annual plant blooms with bright yellow flowers after rainfall. It has a relatively short life cycle, quickly producing seeds before the desert dries out. It obtains nutrients from the soil and provides food for insects and other small animals.

Table: Desert Plant Adaptations

The following table summarizes key adaptations of selected desert plants for survival:

| Plant Species | Key Adaptations | Role in Food Web | Nutrient Acquisition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creosote Bush (Larrea tridentata) | Small, waxy leaves; extensive root system | Food and shelter for rodents, insects | Roots absorb nutrients from soil |

| Saguaro Cactus (Carnegiea gigantea) | Water-storing stem; shallow, spreading roots | Food and shelter for birds, bats | Roots absorb nutrients from soil |

| Prickly Pear Cactus (Opuntia spp.) | Flat pads, spines; shallow roots | Food for desert tortoises, javelinas | Roots absorb nutrients from soil |

| Desert Marigold (Baileya multiradiata) | Short life cycle; rapid seed production | Food for insects, small animals | Roots absorb nutrients from soil |

Primary Consumers (Herbivores) in Desert Food Webs

Primary consumers, or herbivores, play a crucial role in desert ecosystems by converting the energy stored in plants (producers) into a form that can be utilized by higher trophic levels. Their presence and abundance significantly influence the structure and function of the entire food web. The adaptations of these animals to the harsh desert conditions are remarkable and demonstrate the resilience of life in these challenging environments.

Dietary Habits and Feeding Strategies of Desert Herbivores

Desert herbivores have evolved various strategies to survive in environments where food resources are often scarce and unpredictable. These strategies include specialized digestive systems, efficient water conservation methods, and behaviors that minimize exposure to extreme temperatures. Many herbivores are opportunistic feeders, consuming whatever plant material is available, while others have developed specific preferences for certain plants.

Examples of Herbivores and Their Plant Food Sources

Desert herbivores exhibit a wide range of feeding habits, from browsing on shrubs to grazing on grasses and consuming seeds. The availability of different plant types, as well as the specific adaptations of each herbivore, determines their dietary preferences. Some herbivores may also obtain water from their food, further reducing their reliance on external water sources.Here are some examples of primary consumers in desert ecosystems and their unique feeding behaviors:

- Desert Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis): These large herbivores are well-adapted to mountainous desert regions. They primarily browse on a variety of plants, including grasses, shrubs, and cacti. Their strong teeth and digestive systems allow them to break down tough plant material. They often migrate to areas where food is more abundant, following seasonal rainfall patterns.

- Desert Cottontail Rabbit (Sylvilagus audubonii): These rabbits are common throughout the deserts of North America. They are primarily grazers and browsers, feeding on grasses, forbs, and the leaves and stems of shrubs. They are crepuscular, meaning they are most active during dawn and dusk, when temperatures are cooler, to avoid the heat of the day.

- Kangaroo Rat (Dipodomys spp.): These small rodents are highly specialized for desert life. They primarily feed on seeds, which they gather and store in underground burrows. They are incredibly efficient at conserving water, producing highly concentrated urine and obtaining moisture from the seeds they consume. They have cheek pouches to transport seeds efficiently.

- Desert Tortoise (Gopherus agassizii): This long-lived reptile is a herbivore that primarily consumes grasses, wildflowers, and cacti. They have a slow metabolism and can survive for extended periods without water, obtaining moisture from their food. They are adapted to burrowing underground to escape the heat and predators.

- Antelope Ground Squirrel (Ammospermophilus spp.): These diurnal squirrels are active during the day and feed on seeds, fruits, and leaves. They have specialized kidneys that allow them to conserve water effectively. They also have the ability to retreat to the shade of bushes or burrows to escape the intense heat.

Secondary Consumers (Carnivores and Omnivores) in Desert Food Webs: Desert Food Web Examples

Secondary consumers are crucial components of desert food webs, playing a significant role in regulating populations of primary consumers and other organisms. These animals obtain their energy by consuming primary consumers (herbivores) and, in some cases, other secondary consumers. Their presence helps maintain the balance within the ecosystem.

Role of Secondary Consumers

Secondary consumers, consisting of carnivores and omnivores, occupy a critical position in desert ecosystems. Carnivores primarily consume other animals, while omnivores have a diet that includes both plants and animals. Their role is to control the populations of herbivores, preventing overgrazing and maintaining plant biodiversity. They also contribute to nutrient cycling by consuming dead organisms and returning nutrients to the soil.

Hunting Techniques and Prey Preferences

The hunting techniques and prey preferences of secondary consumers vary greatly depending on the species and the specific desert environment. These animals have evolved specialized adaptations to successfully capture their prey.

- Ambush predators, like some snakes, utilize camouflage and patience, waiting for unsuspecting prey to come within striking distance. They may have venom to immobilize their prey.

- Active hunters, such as coyotes, employ strategies like chasing, stalking, and cooperative hunting to capture their food.

- Nocturnal hunters, like owls, use keen senses, including exceptional hearing and night vision, to locate and capture prey under the cover of darkness.

- Omnivores, such as the desert tortoise, are opportunistic feeders, consuming whatever food sources are available, including plants, insects, and carrion.

Examples of Secondary Consumers and Their Primary Food Sources

Numerous species act as secondary consumers in desert ecosystems. Their diets are often specialized to exploit available resources.

- Coyotes are omnivores that prey on rodents, rabbits, birds, and sometimes even insects and fruits.

- Snakes, such as the sidewinder, primarily consume rodents, lizards, and birds.

- Hawks, like the red-tailed hawk, feed on rodents, reptiles, and other birds.

- Owls, such as the great horned owl, are nocturnal hunters that prey on rodents, rabbits, and other small animals.

Table of Secondary Consumers, Prey, and Hunting Strategies

The following table illustrates examples of secondary consumers, their prey, and their hunting strategies in desert environments.

| Secondary Consumer | Prey | Hunting Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Coyote (Canis latrans) | Rodents, rabbits, birds, lizards | Active hunter, opportunistic, cooperative hunting |

| Sidewinder (Crotalus cerastes) | Rodents, lizards, birds | Ambush predator, venomous bite |

| Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) | Rodents, rabbits, snakes, lizards | Soaring, keen eyesight, diving from above |

| Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus) | Rodents, rabbits, birds, snakes | Nocturnal hunter, keen hearing and vision, silent flight |

Tertiary Consumers (Apex Predators) in Desert Food Webs

Apex predators, also known as tertiary consumers, occupy the top of the food chain in desert ecosystems. They are crucial for maintaining the overall health and stability of these environments. Their role involves regulating the populations of other animals, preventing any single species from dominating and thus ensuring biodiversity.

Identification of Apex Predators in Desert Environments

The apex predators in deserts are typically large carnivores that are not preyed upon by other animals within the ecosystem. Their presence and activity significantly influence the structure and function of the desert food web. These predators are often at risk due to habitat loss and human activities.

Role of Apex Predators in Ecosystem Balance

Apex predators play a vital role in maintaining the balance of the desert ecosystem. They control the populations of herbivores and other carnivores, preventing overgrazing or excessive predation on lower trophic levels. This top-down control helps to maintain biodiversity and ecosystem stability.

The removal of an apex predator can trigger a trophic cascade, leading to significant ecological changes.

Examples of Apex Predators and Their Prey in the Desert Food Web

Several apex predators are found in desert environments, each with its own specific prey. These predators are adapted to survive in harsh conditions and play a crucial role in their respective ecosystems. Their dietary habits directly impact the populations of various other species.

Examples of Apex Predators and Their Environmental Impact

Here are some examples of apex predators and their impact on the desert environment:

- Mountain Lion (Puma concolor): Mountain lions, also known as cougars, are apex predators found in various North American deserts. They primarily prey on herbivores such as deer, bighorn sheep, and smaller mammals. Their presence helps to control herbivore populations, preventing overgrazing and protecting plant communities. For example, in areas where mountain lions are absent or their populations are suppressed, deer populations can increase dramatically, leading to increased browsing pressure on vegetation and potentially causing habitat degradation.

- Gray Wolf (Canis lupus): While less common in deserts than in other habitats, gray wolves can inhabit certain desert regions, particularly in North America. They often prey on ungulates like elk and pronghorn. The presence of wolves can reduce the populations of these herbivores, which in turn can benefit plant life and other species in the food web. The reintroduction of wolves into Yellowstone National Park, a semi-arid environment, offers a well-documented case study of how apex predators can reshape ecosystems.

- Coyote (Canis latrans): Coyotes, although often considered mesopredators, can function as apex predators in some desert ecosystems, especially where larger predators are scarce. They have a varied diet, including rodents, rabbits, and occasionally, deer or livestock. Coyotes regulate populations of smaller animals and scavenge on carrion. Their ecological impact is complex, sometimes leading to indirect effects on plant communities by influencing the behavior of herbivores.

- Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos): Golden eagles are aerial apex predators found in many deserts. They primarily hunt small mammals, birds, and reptiles. Their presence helps to control populations of these animals, thus influencing the structure of the food web. They are also scavengers, playing a role in nutrient cycling. Their nesting habits can impact the environment.

Decomposers and Detritivores in Desert Ecosystems

Decomposers and detritivores are vital components of desert food webs, playing a crucial role in nutrient cycling and maintaining ecosystem health. They break down dead organic matter, returning essential nutrients to the soil, which are then available for producers like plants. Without these organisms, the desert would be overwhelmed with accumulating dead plant and animal material, and the cycling of nutrients would cease, severely impacting the entire ecosystem.

Importance of Decomposers and Detritivores

The significance of decomposers and detritivores lies in their function as nature’s recyclers. They ensure that nutrients are not locked up in dead organisms but are continuously recycled and available for use by other organisms.

- Nutrient Cycling: They break down complex organic molecules (like proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids) into simpler inorganic forms that plants can absorb. This process, known as mineralization, is essential for plant growth and overall ecosystem productivity.

- Waste Removal: They eliminate dead plants, animals, and waste products, preventing the buildup of organic debris. This prevents the spread of diseases and keeps the environment clean.

- Soil Formation: Their activities contribute to the formation of humus, a dark, rich organic matter in the soil that improves soil structure, water retention, and aeration.

- Energy Flow: They facilitate the flow of energy through the ecosystem by converting dead organic matter into energy available for other organisms, particularly detritivores, and eventually into the soil.

Decomposition Process in the Desert Environment

Decomposition in the desert is a relatively slow process compared to more humid environments. This is due to the scarcity of water, which is a crucial factor for microbial activity, and the extreme temperatures, which can both inhibit and accelerate decomposition depending on the specific conditions.

- Limited Water: Water availability is the primary limiting factor. Decomposition rates are significantly reduced during prolonged dry periods.

- Temperature Fluctuations: High daytime temperatures can accelerate decomposition, while cold nights can slow it down. Extreme heat can also denature enzymes, hindering microbial activity.

- UV Radiation: Intense sunlight and UV radiation can damage organic matter and inhibit microbial activity.

- Soil Composition: The soil texture and composition affect decomposition. Sandy soils, common in deserts, tend to drain quickly, limiting water availability for decomposers.

- Type of Organic Matter: The composition of the organic matter affects the decomposition rate. Woody plant material, for instance, decomposes slower than soft plant material.

Examples of Decomposers and Detritivores and Their Roles

Various organisms contribute to decomposition and detritus consumption in the desert. Their specific roles vary, but they all contribute to the overall process of nutrient cycling.

- Bacteria: Bacteria are the primary decomposers, breaking down a wide range of organic compounds. They are particularly active in the soil, where they mineralize organic matter, releasing nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus. Example: Bacillus species.

- Fungi: Fungi, especially molds and mushrooms, are also important decomposers. They secrete enzymes that break down complex organic molecules. They are particularly efficient at breaking down cellulose and lignin in plant matter. Example: various Aspergillus species.

- Detritivore Insects: Insects like termites, ants, and beetles consume dead plant material and animal waste. They break down organic matter into smaller pieces, increasing the surface area for microbial decomposition. Example: desert termites ( Gnathamitermes tubiformans).

- Arachnids: Scorpions and some mites are detritivores, feeding on dead insects and other organic debris. They contribute to the breakdown of organic matter. Example: desert mites.

- Nematodes: These microscopic worms feed on bacteria, fungi, and organic matter, further contributing to decomposition and nutrient cycling.

How Decomposers Break Down Organic Matter

Decomposers utilize various mechanisms to break down organic matter. This process typically involves the secretion of enzymes that catalyze the breakdown of complex molecules into simpler forms.

- Enzymatic Degradation: Decomposers, particularly bacteria and fungi, secrete enzymes that break down complex organic molecules like cellulose, lignin, proteins, and carbohydrates. For example, cellulase enzymes break down cellulose.

- Cellulose Breakdown: Fungi like Aspergillus secrete cellulase enzymes that break down cellulose, the main structural component of plant cell walls. This process releases sugars, which the fungi then use as an energy source.

- Lignin Breakdown: Lignin, a complex polymer found in wood, is broken down by specialized fungi, particularly white-rot fungi. This process is slower than cellulose decomposition.

- Protein Breakdown: Bacteria and fungi secrete proteases, enzymes that break down proteins into amino acids. Amino acids are then further broken down, releasing nitrogen and other nutrients.

- Mineralization: The final stage involves the conversion of organic molecules into inorganic forms (mineralization). Bacteria play a critical role in this process, releasing nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium back into the soil.

Specific Desert Food Web Examples

The complexity of desert ecosystems is best understood by examining specific examples. Focusing on a particular desert allows for a detailed exploration of species interactions and energy flow within a defined environment. The Sonoran Desert, known for its rich biodiversity and iconic saguaro cactus, provides an excellent case study for understanding desert food webs.

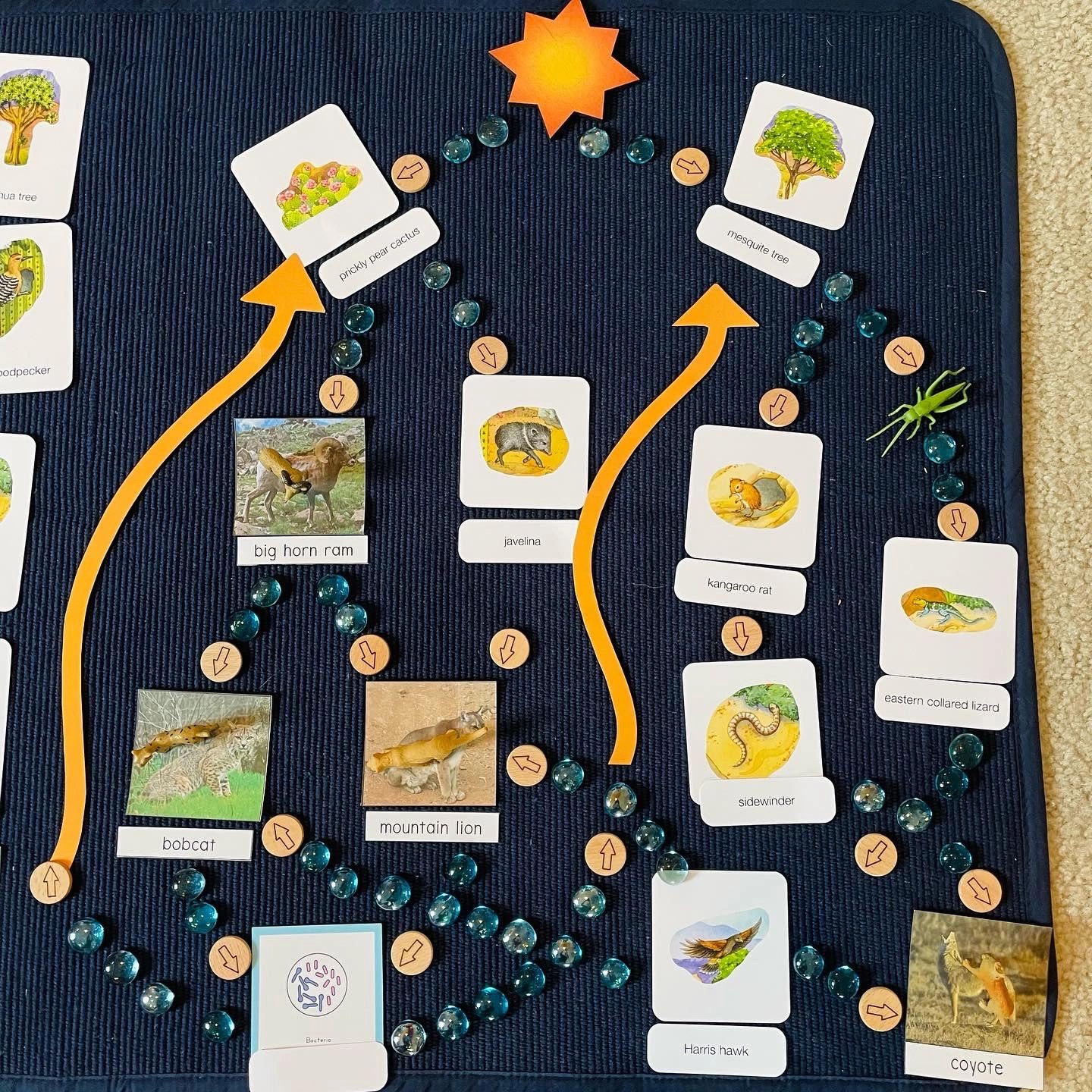

Sonoran Desert Food Web Illustration

The Sonoran Desert food web is a complex network of interacting organisms, from primary producers to apex predators. The flow of energy and nutrients through this web supports a diverse array of life, adapted to the harsh desert environment.The primary producers in the Sonoran Desert are plants, such as the saguaro cactus, various shrubs, and grasses. These plants capture solar energy through photosynthesis, forming the base of the food web.

Primary consumers, including herbivores like the desert bighorn sheep, jackrabbits, and various insects, feed on these plants. Secondary consumers, such as coyotes, roadrunners, and rattlesnakes, prey on the herbivores and sometimes on other carnivores. Apex predators, like the mountain lion, occupy the highest trophic level, feeding on other carnivores and herbivores. Decomposers, including bacteria and fungi, break down dead organic matter, returning nutrients to the soil and completing the cycle.

- Producers: Saguaro cactus, creosote bush, various grasses.

- Primary Consumers (Herbivores): Desert bighorn sheep, jackrabbits, ground squirrels, insects (e.g., grasshoppers).

- Secondary Consumers (Carnivores and Omnivores): Coyotes, roadrunners, rattlesnakes, Gila monsters.

- Tertiary Consumers (Apex Predators): Mountain lions, bobcats.

- Decomposers: Bacteria, fungi, insects (e.g., dung beetles).

Saguaro Cactus, Bats, and Other Species Relationships

The saguaro cactus plays a pivotal role in the Sonoran Desert food web, serving as a primary producer and providing habitat and food for numerous species. Its interactions with bats are particularly significant.The saguaro cactus produces large, white, nocturnal flowers that bloom at night. These flowers are pollinated primarily by bats, particularly the lesser long-nosed bat. The bats feed on the nectar of the flowers, and in the process, they transfer pollen, enabling the cactus to reproduce.

The bats, in turn, benefit from the nectar, providing them with energy. The saguaro cactus also produces fruit, which is a food source for various animals, including birds, rodents, and insects. These animals then disperse the cactus seeds, further propagating the species.

- Bats and Saguaro Cactus: The lesser long-nosed bat pollinates the saguaro cactus flowers, and the cactus provides nectar for the bats.

- Birds and Saguaro Cactus: Birds, such as Gila woodpeckers and gilded flickers, nest in the saguaro cactus and feed on its fruits and insects.

- Rodents and Saguaro Cactus: Rodents, such as the cactus mouse, consume the cactus fruits and seeds.

- Insects and Saguaro Cactus: Various insects, including bees and ants, feed on the nectar and contribute to pollination.

Energy Flow in the Sonoran Desert Food Web

The flow of energy in the Sonoran Desert food web follows a distinct pattern, starting with the sun and passing through various trophic levels. This energy transfer illustrates the interdependence of the species within the ecosystem.

Energy from the Sun → Saguaro Cactus (Producer) → Lesser Long-nosed Bat (Primary Consumer, pollinator) → Coyote (Secondary Consumer) → Mountain Lion (Apex Predator) → Decomposers (Bacteria and Fungi) → Nutrients returned to the soil → Saguaro Cactus (Cycle begins again).

Specific Desert Food Web Examples

The Sahara Desert, the largest hot desert in the world, presents a harsh environment that supports a surprisingly diverse array of life. Understanding the intricate food webs within this arid ecosystem is crucial for appreciating the delicate balance of life and the challenges faced by its inhabitants. This section will delve into the specific food web of the Sahara Desert, highlighting key species and their interactions.

Sahara Desert Food Web Overview

The Sahara Desert food web, like any ecosystem, is characterized by the flow of energy from producers to consumers. The foundation of the food web is formed by producers, primarily plants adapted to survive in the extreme conditions. These plants are then consumed by herbivores, which in turn are preyed upon by carnivores and omnivores. The top of the food web is occupied by apex predators, and the cycle is completed by decomposers that break down dead organic matter.

The relationships within the Sahara food web are complex and highly adapted to the limited resources and extreme climate.

Fennec Fox, Sand Cat, and Their Interactions

The Fennec fox (Vulpes zerda*) and the sand cat (*Felis margarita*) are two fascinating predators that play significant roles in the Sahara Desert food web. Their interactions and those with other species demonstrate the interconnectedness of life in this challenging environment.The Fennec fox, with its oversized ears, is well-adapted to the desert environment. It primarily feeds on insects, rodents, lizards, and occasionally fruits and plants.

Its diet is opportunistic, varying depending on food availability. The sand cat, smaller and more elusive than the Fennec fox, is a nocturnal hunter. Its diet is also diverse, including rodents, birds, reptiles, and insects. Both predators compete for some of the same prey resources, creating a complex dynamic. The Fennec fox’s smaller size and lighter build allow it to navigate the sandy terrain efficiently.

The sand cat’s cryptic coloration and stealthy hunting style make it a formidable predator. The relationship between the two can vary based on resource availability and specific habitat niches.* Predator-Prey Relationships: Both the Fennec fox and the sand cat are predators. The Fennec fox preys on insects, rodents, lizards, and sometimes plants. The sand cat primarily consumes rodents, birds, reptiles, and insects.

Competition

Both species may compete for similar food sources, especially rodents.

Habitat Overlap

Both species inhabit similar desert environments, increasing the likelihood of interaction and competition.

Adaptations

Both species have developed adaptations to survive in the harsh desert climate. The Fennec fox’s large ears help it dissipate heat and locate prey, while the sand cat’s thick fur protects it from the cold desert nights.

Sahara Desert Food Web Levels and Organisms

The following table provides a simplified overview of the different levels of the food web in the Sahara Desert and some of the organisms involved.

| Trophic Level | Organisms | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Producers | Desert shrubs (e.g.,

|

These plants are adapted to the arid conditions and use photosynthesis to create energy. |

| Primary Consumers (Herbivores) | Various insects (e.g., grasshoppers, beetles), rodents (e.g., gerbils, jerboas), desert reptiles | These organisms feed on the producers, consuming plant matter. |

| Secondary Consumers (Carnivores and Omnivores) | Fennec fox, sand cat, various reptiles (e.g., desert monitor), birds of prey (e.g., eagles, hawks) | These organisms consume primary consumers. The Fennec fox and sand cat, in particular, occupy this level. |

| Tertiary Consumers (Apex Predators) | Larger birds of prey, occasionally other carnivores | These predators are at the top of the food chain and typically have no natural predators within the desert ecosystem. |

| Decomposers and Detritivores | Bacteria, fungi, insects (e.g., some beetles) | These organisms break down dead organic matter, returning nutrients to the soil. |

Adaptations in Desert Food Webs

Organisms in desert food webs have evolved a remarkable array of adaptations to cope with the harsh conditions of extreme temperatures, scarce water, and intense sunlight. These adaptations are crucial for survival and play a vital role in maintaining the stability and complexity of the food web.

Without these specialized traits, the desert ecosystem would be significantly less diverse and less resilient to environmental changes.

Behavioral Adaptations

Behavioral adaptations involve changes in an organism’s actions to improve its chances of survival. These adaptations can be as simple as altering the time of day an animal is active or as complex as developing social structures that enhance foraging efficiency.

- Nocturnal Activity: Many desert animals are primarily active at night (nocturnal) to avoid the intense daytime heat. This behavior reduces water loss through evaporation and minimizes exposure to solar radiation. For example, the kangaroo rat, a common desert rodent, spends its days in cool, humid burrows and emerges at night to forage for seeds. This strategy allows it to avoid the harshest conditions of the day and conserve precious water.

- Migration: Some desert animals migrate to areas with more favorable conditions during periods of extreme drought or resource scarcity. This allows them to access food and water resources that are unavailable in their usual habitat. The pronghorn antelope, found in North American deserts, is known for its long-distance migrations in search of food and water, particularly during dry seasons.

- Burrowing: Burrowing provides a cool, stable microclimate and protection from predators. Many desert reptiles, mammals, and insects spend a significant portion of their time underground. The desert tortoise, for instance, digs extensive burrows where it can regulate its body temperature and conserve water. These burrows can also serve as refuges during wildfires or extreme weather events.

Physiological Adaptations

Physiological adaptations are internal processes that help organisms survive in the desert environment. These adaptations can include efficient water conservation mechanisms, specialized digestive systems, and the ability to tolerate extreme temperatures.

- Efficient Water Conservation: Many desert animals have evolved remarkable water conservation strategies. These include producing highly concentrated urine, reducing water loss through respiration, and extracting water from their food. The camel, for example, can tolerate significant water loss and produces very concentrated urine and dry feces. This allows it to survive for extended periods without access to water.

- Tolerance of High Temperatures: Desert organisms have developed various mechanisms to tolerate extreme temperatures. Some animals, like the jackrabbit, have large ears that act as radiators, dissipating heat through blood vessels near the surface. Others, such as the desert pupfish, can survive in water with high salinity and temperatures exceeding 40°C (104°F).

- Metabolic Adaptations: Certain desert organisms possess unique metabolic pathways that aid in survival. Some insects, for example, can extract water from the air through a process called condensation. This allows them to obtain moisture even in extremely arid conditions.

Morphological Adaptations

Morphological adaptations refer to physical characteristics that enhance survival in the desert. These adaptations can involve changes in body size, shape, color, or the presence of specialized structures.

- Camouflage: Many desert animals exhibit camouflage to blend in with their surroundings, providing protection from predators or aiding in hunting. Desert reptiles, like the sidewinder snake, have coloration that matches the sand and rocks, making them difficult to spot.

- Reduced Surface Area: Some desert animals have evolved body shapes that minimize surface area to volume ratio, reducing heat absorption. The fennec fox, with its large ears, is an exception, as the ears act as radiators. However, many desert animals, like the desert bighorn sheep, have compact bodies.

- Specialized Structures for Water Acquisition: Some plants and animals have developed specialized structures for collecting or storing water. The saguaro cactus, for instance, has a large, ribbed stem that expands to store water after rainfall. Similarly, the desert tortoise has a bladder that can store large amounts of water.

Threats to Desert Food Webs

Desert food webs, delicately balanced ecosystems, are increasingly threatened by a variety of factors, primarily driven by human activities and climate change. These threats can cascade through the food web, impacting species from the smallest decomposers to the apex predators, potentially leading to significant biodiversity loss and ecosystem instability. Understanding these threats is crucial for implementing effective conservation strategies.

Climate Change Impacts

Climate change poses a significant threat to desert food webs. Rising temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and increased frequency of extreme weather events are disrupting the delicate balance of these ecosystems. These changes impact both the availability of resources and the survival rates of various species.

- Increased Temperatures: Rising temperatures can lead to heat stress in many desert animals, reducing their activity, reproductive success, and overall survival. For example, increased heat can lead to reduced foraging time for desert rodents, making them more vulnerable to predation. Higher temperatures can also exacerbate water scarcity.

- Altered Precipitation Patterns: Changes in rainfall, including decreased overall precipitation or more erratic rainfall patterns (such as longer periods of drought followed by intense, short-lived rainstorms), can significantly affect plant growth. This in turn affects primary consumers that depend on those plants, and so on up the food chain. Prolonged droughts can decimate plant populations, leading to widespread starvation among herbivores, and subsequently impacting carnivores.

For example, the decline in certain plant species due to drought can reduce the food available for desert tortoises, impacting their population size.

- Extreme Weather Events: More frequent and intense heat waves, flash floods, and dust storms can cause direct mortality of animals and disrupt habitats. Intense rainfall can lead to erosion and habitat destruction, while dust storms can reduce visibility and impact plant photosynthesis. For example, severe dust storms can suffocate small animals or damage plants, reducing the base of the food web.

Habitat Destruction and Fragmentation, Desert food web examples

Habitat destruction and fragmentation are major threats to desert food webs, often resulting from human activities such as agriculture, urbanization, mining, and infrastructure development. These activities reduce the amount of available habitat and can isolate populations, making them more vulnerable to extinction.

- Habitat Loss: Converting desert land for agriculture or urban development directly removes habitat, eliminating resources like food and shelter for native species. This loss can lead to population declines and local extinctions. For instance, the expansion of agricultural lands in the Sonoran Desert has led to a reduction in the habitat available for the desert bighorn sheep.

- Habitat Fragmentation: Fragmentation occurs when large, continuous habitats are broken up into smaller, isolated patches. This can restrict animal movement, limiting access to food, water, and mates. Isolated populations are also more susceptible to genetic bottlenecks and increased vulnerability to local disturbances. The construction of roads and fences can fragment desert habitats, preventing animals like coyotes and kit foxes from accessing different parts of their home ranges, hindering their ability to find food and mates.

- Introduction of Invasive Species: The introduction of non-native plants and animals can disrupt desert food webs. Invasive species often outcompete native species for resources, alter habitat structure, and can even prey on native species. For example, the introduction of buffelgrass in the Sonoran Desert has increased fire frequency and intensity, which favors the invasive grass over native plants, altering the plant community and impacting the animals that rely on those native plants.

Pollution and Resource Depletion

Pollution and resource depletion, stemming from human activities, also affect desert ecosystems. These issues directly impact the health of desert species and the availability of crucial resources.

- Pollution: Pollution, including pesticides, herbicides, and industrial waste, can contaminate water sources and soil, harming plants and animals. These toxins can bioaccumulate in the food web, with the highest concentrations found in apex predators. For instance, the use of pesticides in agricultural areas can contaminate water sources used by desert animals, leading to poisoning and mortality.

- Overgrazing: Excessive grazing by livestock can degrade vegetation, leading to soil erosion and habitat loss. This directly impacts primary producers and subsequently the entire food web. Overgrazing in the arid regions of the southwestern United States has reduced the abundance of native grasses, impacting the populations of desert rodents and the predators that depend on them.

- Overexploitation of Resources: Unsustainable harvesting of plants and animals can deplete populations and disrupt food web dynamics. This can include the over-collection of plants for medicinal purposes or the hunting of animals for food or the pet trade. For example, over-collection of cacti for the horticultural trade can reduce food sources for desert animals, like the desert tortoise, and also alter the structure of the habitat.

Ending Remarks

In conclusion, studying desert food web examples provides a compelling insight into the resilience and interdependence of life. These ecosystems, despite their apparent simplicity, are complex tapestries woven with the threads of adaptation, survival, and ecological balance. Understanding these webs is crucial not only for appreciating the natural world but also for recognizing the threats these delicate systems face and the importance of conservation efforts in preserving these unique and vulnerable habitats.

By examining the diverse interactions within these environments, we gain a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness of all living things and the importance of protecting biodiversity.