How far behind the curve is the FOMC?

I'm in the final month of my book vacation, but felt compelled to stop by at what seems like a pivotal time in the economic/market cycle to discuss how we got here and what the impending rate cuts might mean for the future.

A quick caveat: the world is always more complex and nuanced than we see in the media or science. There are millions of little unknown details, and our penchant for narrative fallacies leads to clear and compelling storylines that often lack credibility.

Let's start at 30,000 feet before we focus on the details. After the financial crisis, ZIPR/QE pushed interest rates to 0%, there was hardly any fiscal stimulus,1 and so the decade of recovery following the global financial crisis in the 2010s was characterized by weak job creation, low wage growth, low consumer spending, and modest GDP. Inflation was non-existent, and CASH was king.

This is what the post-financial crisis period has historically looked like – except for the times when governments apply the lesson of fiscal stimulus we learned from Lord Keynes to stimulate economic expansion.

The pandemic has caused numerous supply problems, but as with so many other things in the world, the causes of these problems go back years or decades:

– Overconstruction of single-family homes in the 2000s led to an underconstruction of single-family homes from 2007 to 2021. A reasonable estimate is that the United States needs 2 to 4 million single-family homes, especially inexpensive entry-level homes.

– While just-in-time deliveries may have resulted in a few cents more in earnings per share (not insignificant), the price for this was instability, which led to massive shortages of essential goods, especially in the healthcare sector.2

– The labor shortage dates back to 9/11, when the Bush administration changed the rules about who could stay in the United States after graduating from college. This was followed by a drop in legal immigration, a rise in disability, COVID-19 deaths, and early retirement. A reasonable estimate is that the United States needs 2-4 million additional workers to fill our workforce and completely reduce wage pressures.

The delay in the resumption of semiconductor production, which led to a rise in the prices of new and used cars, was a major factor in the first round of price increases.

Finally, I have to mention greedflation.3 When the term first came up, I was skeptical and naively believed that companies only raised their prices when they were forced to do so in order to avoid losing the favor of customers in the long run.

My views have evolved since then.

The term is defined as companies taking advantage of the general chaos surrounding a rise in inflation to raise prices far more than their input costs have risen. It is not price gouging. per sebut a more general “Hey, everyone else is raising prices, why not us?” If the goal of corporate management is (one could argue) to maximize profits, then many companies have been very successful in putting price before quantity.

Earnings hit an all-time high and helped propel the stock market to an all-time high as it climbed the wall of worry and chronic bears and skeptics.

~~~

Added to this complex mess is a once-in-a-century pandemic.

A few weeks earlier, Congress in Washington, DC, had argued over renaming some schools/libraries (which didn't happen). Then the NBA canceled live games, and a spate of shutdowns across the economy followed.

The country and most of the world stand still.

Fear mounted rapidly. The inability to pass even the most basic legislation gave way to panic, and Congress passed the CARE Act (I), the largest economic stimulus package in terms of GDP since World War II.

Most observers were optimistic, but Jeremy Siegel, a professor of finance at the University of Pennsylvania, deserves all the credit for presciently noting that such a massive fiscal stimulus would lead to a huge, if temporary, increase in inflation.

And he was right.

With people working from home and the service sector partially temporarily closed, consumers have shifted to consuming goods. Our 60/40 economy has become a 40/60 economy. If you give generous stimulus checks to people stuck at home, the result will be a huge demand for goods, driving up prices every time.4

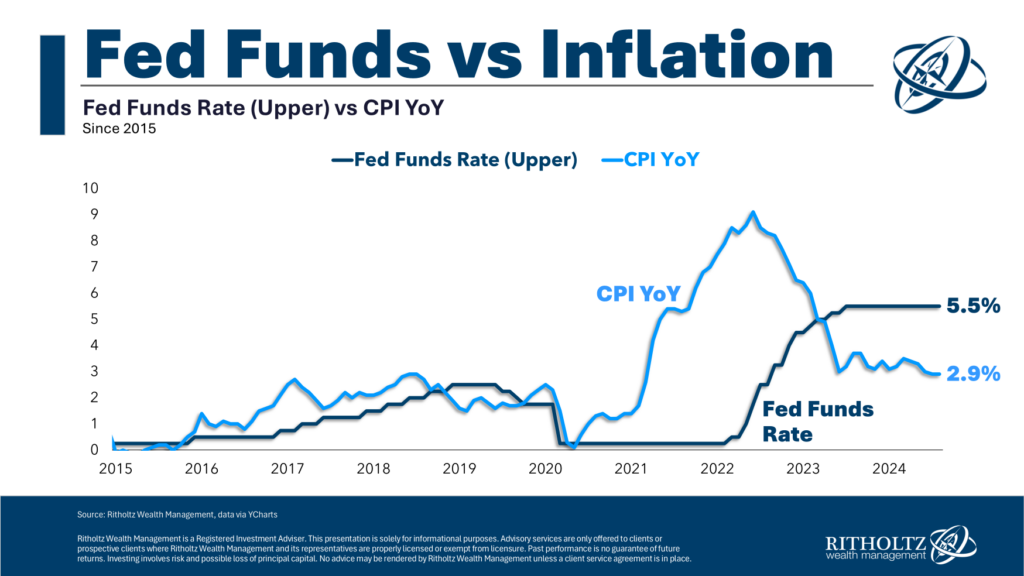

Inflation exceeded the Federal Reserve's 2% target in March 2021; in December 2021, the consumer price index was above 7%. It peaked at 9% in June 2022. Inflation fell almost as quickly as it had risen.

By June 2023, it was clear to any observer who understood how the BLS models worked that inflation had been defeated. The consumer price index fell to about 3%, but that figure was a bit too high because it included a lot of lagged data on housing and rents.

The Fed is a large, stubborn institution that is conservative by nature. It moves slowly. Its incentive structure is asymmetric: it is much more concerned with “not being wrong” than with “being right.”

This complexity is not quite as contradictory as it may sound.

Consider the possibility of rate cuts in June 2023 (as I advocated at the time). If they had cut too early and inflation flared up again, they would have looked foolish. If it had not been too early, all they would have accomplished is: credit relief for the entire bottom 50% of consumers; increased housing supply; stimulated capital spending; encouraged more hiring; maintained economic growth.

But here's the thing: they would have received absolutely no credit for this result. It was a modest risk with no benefits for them.

So they preferred to play it safe and wait until it was more than obvious that inflation was dormant and the economy was cooling down.

We can debate whether the FOMC should have started cutting interest rates in June 2023 (perhaps a touch earlier) or September 2025 (obviously late).

Regardless, there will be interest rate cuts. They are probably already priced into stock prices, which points to another concern of Jerome Powell's: he does not want to allow the AI hype to grow into a real bubble. But we will have to talk about that another time.

Enjoy the rest of your summer!

Previously:

Why the Fed should start cutting interest rates already (May 2, 2024)

The increase in the consumer price index is based on poor housing data (January 11, 2024)

The Fed is finished* (November 1, 2023)

Who is to blame for inflation, 1-15 (June 28, 2022)

Inflation falls despite Fed (January 12, 2023)

Why is the Fed always late to the party? (October 7, 2022)

The economy after the lockdown (November 9, 2023)

How everyone misjudged housing demand (July 29, 2021)

_________

1. At the time, I attributed the lack of robust fiscal action to “partisan sabotage,” but that was widely dismissed by both left and right. CARES Acts 1 and 2 (under Trump) and 3 (under Biden) have only served to confirm that previous observation: We know what the right playbook looks like; when we fail to implement it, it is usually for the wrong ideological and political reasons.

2. This is a national security issue and I support the federal government's commitment to maintaining a 90-180 day supply of products essential to the nation's health and welfare. If all companies MUST have a 3 month supply of widgets, it shouldn't affect stock prices except for who is most efficient at putting together a supply. And there are heavy penalties for stockpiling cheap, foreign-made junk that won't work when needed.

3. And its cousin, shrinkflation.

4. By the end of 2021, vaccines were widely available and the end of the pandemic was in sight. What followed was a summer of revenge travel, higher spending on services, and a slow, if not almost, return to normality.